For the last two years, I have run this piece on October 25th. It’s called ON POLAROIDS AND LASTING FRIENDSHIP. Tonight some of Jamie’s friends are getting together to toast their friend — OTBKB

For the last two years, I have run this piece on October 25th. It’s called ON POLAROIDS AND LASTING FRIENDSHIP. Tonight some of Jamie’s friends are getting together to toast their friend — OTBKB

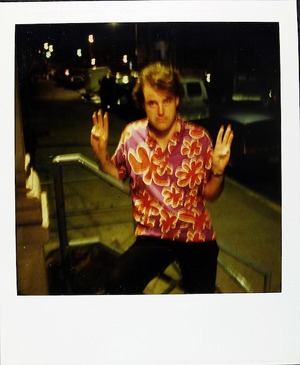

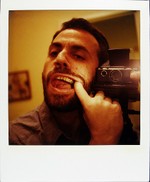

When Jamie Livingston, photographer, filmmaker, circus performer,

accordian player, Mets fan, and above all, loyal friend, died

on October 25th (his birthday) in 1997 at the age of 41, he left behind

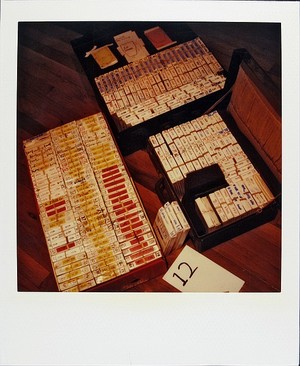

hundreds of bereft friends and a collection of 6,000 photographs neatly

organized in small suitcases and wooden fruit crates.

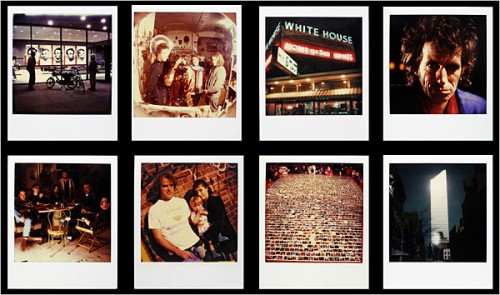

Jamie took a polaroid once a day, every day, including his last, for 18 years.

This

photographic diary, which he called, “Polaroid of the Day,” or P.O.D.,

began when Jaime was a student at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson.

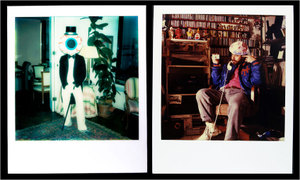

The project continued when he moved to apartments in New York City

including the incredible circus memorabelia-filled loft on Fulton

Street, which he shared with his best friend Chris Wangro. That loft was the site of

many a Glug party, an “orphans thanksgiving,” a super-8 festival of

Jamie’s lyrical films, and a rollicking music jam.

The picture

taking continued as Jamie traveled the world

with the Janus Circus, the circus-troupe founded by Chris Wangro,

and later when he became a much-in-demand

cinematographer and editor of music videos back in the early days of

MTV. He contributed his talents to the ground-breaking Nike

“Revolution” spot and many other commercials, too. Through it all he

took pictures, made movies, and loved his friends. And the polaroids

reflect all of that: a life bursting with activity, joy and sadness, too.

Jamie brought his camera wherever he went. As one friend

said, “It probably helped his social life because everyone wanted to be

in a photo of the day.” It was always interesting to see what Jaime

deemed worthy of a P.O.D. My husband remembers his own 30th birthday party

in his photo studio on Ludlow Street: “Hundreds of people filled my

loft and the party snaked down Ludlow Street to Stanton. But what did

Jamie take a picture of? A potato chip or something. It was a gorgeous

shot, though.”

But more often than not, the photos were of

friends, family, himself, special places he had visited, or just

something that caught his discriminating eye. And if he’d been to a

Mets Game that day, that was it — a Mets game was always a worthy

P.O.D.

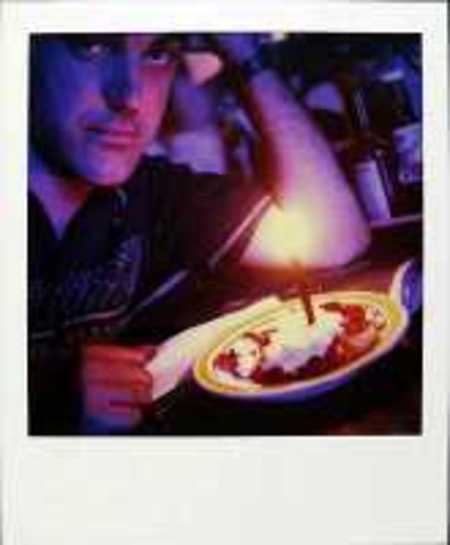

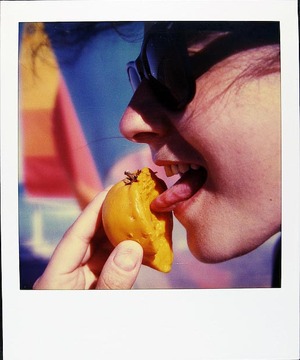

And the pictures are utterly gorgeous miracles of

photographic artistry. The color, the light, the time lapse swirls, the

unerring composition. Whether it was a still life of what he’d eaten

for dinner, an unblinking shot of his beloved grandfather (Pops), or

swooningly romantic portraits of his beautiful wife or ex-girlfriends,

any one of these photographs should be in a museum collection. But

perhaps more importantly, Jamie’s friends and the world need access to

these pictures, which is why his devoted friends have been talking for

years about ways to exhibit this massive body of work.

Back in

September at a bris for the son of a good friend, HC and our friend Betsy, one

of Jamie’s still devoted ex-girlfriends, started talking about the

P.O.D.s: “Why don’t we finally re-photograph all 6,000 of

them and put them on a web site.” And that’s practically what they did.

They spent many October days digitally re-photographing the picures.

This labor of love was also exceedingly labor intensive and they only

got up to 1990 (the P.O.D.s started in 1978). But they plan to finish the

rest when they have some time again.

A year ago today there was a “Jamie Fest,” a

commemoration of the seventh anniversary of his death, a small group of

friends gathered at the envy-inducing loft of one of Jamie’s oldest,

dearest friends in Tribeca and were treated to a veritable feast of

PODs, films, good red wine, beer, and Chinese food. There was a warmth

in that room, a convivial feeling of purpose, as the friends remembered

their friend who left behind a journal of his life and their’s too.

HC set up a random, non-chronological slide show of these pictures, as

well as a special “computer station” where Jamie’s friends could browse

the well-indexed shots year-by-year, month-by-month, day-by-day.

Hunched over the computer,some pictures made them sad, some made them

reflective, some made them very, very quiet. Others made them laugh or

squeal with recognition of an almost forgotten face, a wonderful

memory, a special time too, too long ago.

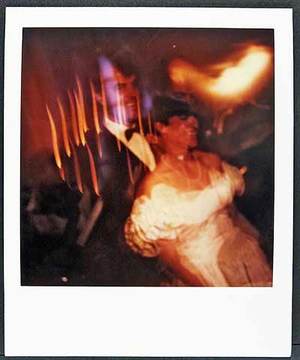

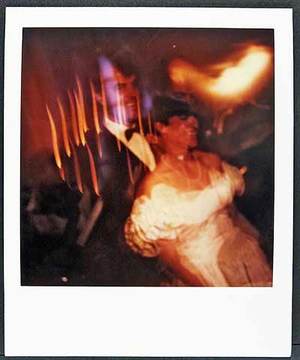

Jamie was the best

man at our wedding. He was HC’s treasured co-hort since their

days at Bard College. I met Jamie soon after

meeting Hepcat, probably at the Great Jones Cafe, and always enjoyed

our group adventures, including the annual walk of the elephants down

34th Street when the Ringling Brothers Circus arrived in town, the

trips to photo shows to buy cameras and old photographs, their brunches

at the Cottonwood Cafe, or seeing the Mets, and the Rolling Stones’

Steel Wheels tour at Shea Stadium. I remember when Jamie

visited me at the hospital when I was having pre-term labor with my son

and nearly lost him. I remember how he and Betsy carried a heavy gift

of a vintage toy box to my son’s first

birthday party in Prospect Park.

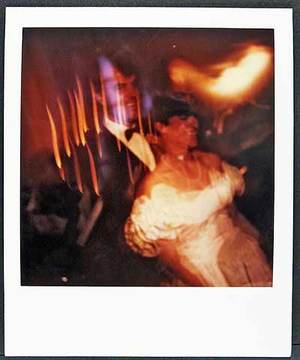

At the “Jamie Fest” last year in 2004 I located the stunning P.O.D. of our

wedding day and

marveled at how young and thin I was back then (marriage and kids

really ages you). My husband looked so young and

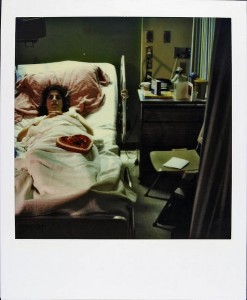

handsome in his father’s tuxedo. I also found the picture from the

night before the wedding when Jaime and Betsy joined at the emergency

room at Beth Israel Hospital because my husband thought he had a broken

his neck in a minor (okay major) car accident a

few days before the wedding (pre-wedding nerves, no doubt).

Jaime

and Betsy sat with us from mid-night until five a.m., while we waited

for my husband’s neck to be X-Rayed. It turned out that he had a nasty

case of whiplash and had to wear a neck brace at the wedding.

When I suggested that Jamie and Betsy go home to get some sleep,

Jaime refused to budge saying, “I’m your bestman. This is part of my

job.”

On this the 8th 9th anniversary of Jamie’s death: Thank you, Jamie, for being our bestman. And thanks for

giving us a stunning portrait of our lives. You gave us more than you

can ever know.

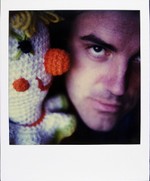

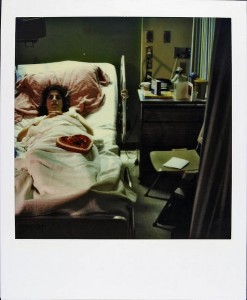

I just found this photo of me on Jamie Livingston’s Photo of the Day website from February 14, 1991.

I just found this photo of me on Jamie Livingston’s Photo of the Day website from February 14, 1991.