Brooklyn author, Richard Grayson, remembers that day 40 years ago:

I can remember exactly where I was around on the Thursday evening forty years ago when, as a 16-year-old high school senior, I heard the news that Martin Luther King Jr. was shot. It was around 7:20 p.m. and I was lying on the floor of my tiny bedroom in our house in Flatlands, my loose-leaf notebook in front of me, half-trying to answer some end-of-chapter questions for my social studies class (History of Latin America) at Midwood, half-watching channel 2’s CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite.

The day’s main news over, they’d switched to a human interest story about a carpenter in England who’d designed a table he thought could be used at the Paris peace talks on Vietnam. The talks had been stalled for months on the famous “shape of the table,” how to seat all the parties: the U.S., North Vietnam, South Vietnam and the Viet Cong.

Suddenly the filmed report (no videotape back in 1968) stopped in the middle and Walter Cronkite was onscreen, reading wire copy of the breaking news of Dr. King’s assassination in Memphis.

As I’d done five years before when, home sick from school, watching Nancy and Grandpa Hughes on “As the World Turns” when it got interrupted by Cronkite in shirtsleeves and wearing unfamiliar clunky black-framed glasses, shakily announcing the shooting in Dallas, I screamed for my parents.

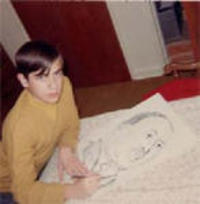

As a kid, I worshipped Martin Luther King Jr. A couple of summers before, working as the cashier in my uncle’s pants store on Fulton Street, I sold pen-and-ink drawings of Dr. King I’d made, amateurish copies of a Time Magazine cover done by Ben Shahn, to some of our customers. (See “The Boy Who Could Draw Dr. King”).

As I write in that piece, King’s assassination devastated me:

I was depressed and too scared to go to school for the next week. There were riots. For some reason I wrote a letter expressing my sorrow and fear and sent it to Percy Sutton, the Manhattan borough president and the top black official in the city. His chief of staff called my mother while I was out and told her I’d written a beautiful letter. All I can remember about it is that I ended by quoting a corny speech from Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar” (I’d read it in Mrs. Sanjour’s ninth grade English class at Meyer Levin Junior High) that went:

His life was gentle, and the elements

So mix’d in him that Nature might stand up

And say to all the world “This was a man!”

This morning I read the rave review of the new Lincoln Center production of one of my favorite musicals, “South Pacific.” The summer before King’s assassination, on July 4, my parents took me and my brothers, who were 12 and 6, to a holiday matinee of Lincoln Center’s last production of “South Pacific.”

We sat in the third row center of the New York State Theatre’s orchestra, close enough that I could see that the star, Florence Henderson as Nellie Forbush, had cellulite on the back of her thighs. For me, every song in that show is a classic, but I mostly remember Henderson’s real shampoo in “Gonna Wash That Man Right Out of My Hair,” Giorgio Tozzi’s operatic “Some Enchanted Evening” and David Doyle’s comic turn as Luther Billis, cavorting in drag in grass skirt with coconut breasts.

But forty years after April 4, 1968, most of all I can recall the young actor playing Lt. Cable’s rendition of what at 16 I thought of as Rodgers and Hammerstein’s corniest song:

You’ve got to be taught to hate and fear

You’ve got to be taught from year to year

It’s got to be drummed in your dear little ear

You’ve got to be carefully taught

You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late

Before you are six or seven or eight

To hate all the people your relatives hate

You’ve got to be carefully taught