Since many OTBKB readers don’t read the conservative New York Sun, I thought I’d alert you to reporter Laura Mechling’s bashing of the Park Slope Food Coop called: Welcome Shoppers, but Please Don’t Paw the Persimmons.

The Sun only lets you read an short excerpt from articles on-line if you’re not registered and I haven’t bothered to register although I do like to see what the Sun has to say most every day. I particularly appreciate their arts coverage and daily calendar.

Thanks to a friend, I now hve the complete text of the Sun article. The reporter obviously went looking for the coop cliche – militant crunchies who have no tolerance for those who don’t want to follow the rule. Instead she found slightly boring and tired coop workers with little to do. It was her first day at work afterall. From my reading, the worst thing she can say about the coop is that she had a hard time striking up a conversation with her fellow workers.

She didn’t really get her story, did she? The story she wanted to tell about the "Granola Nazis" she’d heard so much about.

The Park Slope Food Co-Op is thought

by many to be a terrifying place, a netherworld of rules and suspensions and

withering stares if you forget to bring your own biodegradable shopping bag.

The one time I’d gone there, as somebody’s guest, when I reached out to pick up

a persimmon only to be scolded by a dutiful member, who must have been

following me through the aisles the whole time. "Excuse me," she

said. "Guests aren’t allowed to handle the produce."

Richard, leader of a recent Sunday

afternoon orientation session, was so determined to present the Co-Op’s gentler

side that he had set up a table with organic treats such as carrots and humus

and peach nectar for 30 prospective members. Before getting into anything as

off-putting as regulations or free-range ethics, he started off the meeting by

telling us how much the Co-Op has improved his life. "My ingestion has

really changed," he said. "I’m juicing now!"

Founded in 1973, the Park Slope Food

Co-Op is the oldest and largest member-run food co-op of the approximately 300

in the country. Membership, currently at 12,000, has been growing at an annual

rate of 20% in the past five years, with no sign of slowing down. The store

reaps an annual gross of $20 million. It sells half a ton of bananas a day.

People join because the prices are

cheap and the food is fresh and healthful. The organic radishes and plastic

wrapped cheeses at the Park Slope Food Co-Op cost about half what they would at

a regular health food store, but customers pay for it in other ways. For starters,

there are the rules – no eating in the store, no joining if your spouse or

roommate won’t join, no buying an apricot for a non-member friend. The

cornerstone of a membership to the organic-opolis is the mandatory shift: In

exchange for shopping rights, members work, for free, for nearly three hours

every month. In addition, the store makes prospective members sit through an

orientation session that lasts nearly as long as one of the work shifts.

The range of jobs covers the gamut,

including bookkeeping, "sign committee," putting on an anti-frostbite

suit and tidying up the freezer, and unloading boxes from the backs of trucks.

In my circle, the "food packaging" shift is known as one of the

better (that is, less rigorous) ones, so long as you don’t mind wearing a

hairnet and spending an extended period in a Brooklyn basement.

At most times, the Co-Op’s main

floor doesn’t look that different than a regular health food store, its aisles

crammed with everything from organic almond butter to blueberry tofu knishes.

The basement feels markedly different, more like a kindergarten classroom, with

its annoyingly bright lighting and finger-paint smell. To add to the babyish

atmosphere, labels are attached to every hook, drawer, box, shelf, and door.

The cards say such things as "Orange Spice Tea" and "Tape and

Scissors," and, above two long brooms, two regular brooms, and a dustbin,

a sign reads, "Two long brooms, two regular brooms, and one dustbin on

these hooks."

They like their order at the Co-Op.

Frightened of getting into trouble on my first day as a member, I arrived early

and waited for the rest of my team to show up. The next arrival, a drowsy-eyed

beauty named Susannah, told me that Marty, our squad leader, was out for the

day, so we could have slept in. "It’s not going to be that

different," she said. "There’s never much that needs to be

done."

The next two people to turn up,

Jazmin and Sheldon, both put on the required aprons and started diligently

filling small plastic bags with tea and listening to the mayoral candidate C.

Virginia Fields talk about small businesses on a morning radio show. Sheldon

was shy and tall, and he wore his dreadlocks under a puffy hat. Jazmin’s mouth

remained cast in a frown as she listened to Ms. Fields talk about economic development.

"I don’t trust any politicians," Sheldon said, emptying another scoop

of tea into a bag.

Susannah went upstairs with a

clipboard to see if anything in the "packaged foods" section needed

replenishing, and Sheldon showed me how to package bulk tea, which wasn’t hard.

All you had to do was scoop loose tea into the little bags, then fasten them

shut with a red twistie, and finally weigh and price them with a digital scale

that prints out stickers.

Susannah returned with her notes.

The one thing they were out of upstairs, sun-dried tomatoes, was the one thing

they were out of downstairs. Everything else in the store was at least half

stocked. "See?" she said. "There’s really not much to do."

Soon Gabriella, a serious sort with

glasses and short black hair, showed up, and she took it upon herself to visit

the cheese case upstairs to see if anything was out of stock. She returned,

seeming slightly downcast, to report that nothing was immediately needed.

Lucky for her, even when there’s

nothing that desperately needs to be refilled, there are always huge bulk

items, such as logs of cheese, to be cut, and there are garbage bags of dried

figs to be redistributed into little household-friendly portions. I got to work

on a huge brown paper bag of Earl Grey tea while Gabriella used a wire to cut

Muenster cheese into triangular and rectangular hunks.

The shifts last two hours and 45

minutes, which didn’t seem that long when I’d signed up. Not even an hour into

my shift, though, I started to feel bored and panicked. Everyone remained

quiet, and when I tried asking people questions – how long they’d belonged,

what their favorite Co-Op items are – they gave me dead-weight answers like

"six months" and "herbed tofu spread." Eventually, thankfully,

Sheldon warmed up to me, and we got to talking about his twin daughters and the

Rasta way. He even put down his silver scoop to pull up his apron and show me

the lion on his T-shirt. Time started to pass a little faster.

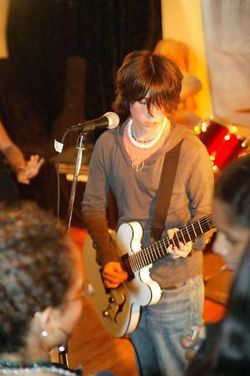

About two hours into our shift, two

members in our squad, an older woman with a peppy attitude and a teenage boy

with a tangle of curls, showed up. The boy wandered away, never to be seen

again, and the woman took a seat at the table and worked on her muffin and

coffee.

Jazmin changed the radio to lite FM

and everyone started to sway to Lionel Richie’s "All Night Long."

"How very un-Co-Op," a

woman who had just materialized declared, holding a watermelon close to her

chest.

"Another customer and I want to

split this," she explained, and she used Gabriella’s cutting board to

slice the fruit.

When she left, Gabrielle let it be

known that she didn’t appreciate the hijacking of her workstation.

"Well, her watermelon was too

light inside. It didn’t look very juicy," Jazmin said, and everyone else

agreed, which seemed to make Gabriella feel better.