Last year at this time, I wrote this post about Sukkot. Actually, it was really about my irritation with the Lubavitch men and women who stop me on the street and say, "Are you Jewish?" I haven’t seen any of them this year – today will probably be the DAY. This year, I plan to say, "Yes I am Jewish, and I don’t want to touch your Lulav." Let’s see how that goes.

Yesterday, I found myself irritated by the Lubavitch men on Seventh

Avenue. Walking home at 6 p.m., I was asked at least five times by

different groups of men: "Are you Jewish?" Each time I said "No" and

they seemed to believe me. Maybe it’s the blonde hair. Surprisingly,

they didn’t seem to flinch at all when I said: "No."

As a kid in a secular Jewish family, I loved the idea of Sukkot. I

knew what it was even though my Jewish education was somewhat spotty.

Building a Sukkah, a make-shift structure, out of branches, leaves,

shrubs, and straw seemed so cool. Who wouldn’t want to create a

beautiful little playhouse in the courtyard of our apartment building

or in Riverside Park.

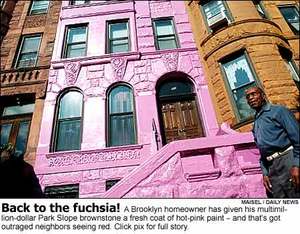

In Park Slope, Sukkot means that there’s a rather impressive Sukkah

at Chai Tots on the corner of Prospect Park West and Third Street and

the men from an extremely evangelical wing of hasidic Judaism, the

Lubavitch sect, are out in droves in their dark suits trying to

pursuade Jews to shake the lulav.

Most of the Jews I know have figured out a usable response to the

question from the men on the street. One friend says: "Yes I’m Jewish

but I already shook the lulav today." Another friend says: "Yeah, I’m

Jewish and please leave me alone."

Lubavitch Hasidism is an international movement with headquarters in

Brooklyn. They focus on transmitting to others Jews the Torah way of

life and operate an extensive outreach effort to encourage a return to

traditional practices. Their Mitzvah Tanks are a frequent sight in New

York City.

My "Just Say No" tactic makes me very uncomfortable. I don’t like to

deny my heritage or hide who I am. We didn’t survive the holocaust to

lie to other Jews on Seventh Avenue about our identities. But it’s a

quick and easy way to be left alone. My irritation almost made me

forget the way I used to marvel at this holiday. And it got me thinking

about what the holiday is all about.

Google is a wonderful thing. When I got home, I sat down at the

computer and in five seconds flat I arrived at Judaism 101 and got the

answers I was looking for. (I hear there’s also something called rabbi.com

for just these kind of questions.) I’ve also got the book I bought my

son for his 13th birthday: "The Jewish Book of Why," which is chock

full of interesting Jewish religious facts. So here goes:

A lulav consists of fours species: a lemon, a palm branch (in Hebrew, lulav), two willow branches, and three myrtle branches.

The lulav must be waved in all six directions (east, south, west,

north, up and down), symbolizing the fact that God is everywhere. This

ritual is a key element of Sukkot, also known as the feast of the

tabernacles, which begins on the fifth day after Yom Kippur. Unlike Yom

Kippur, which is one of the most most solemn days of the year, Sukkot

is a joyful holiday and sometimes referred to as the season of

rejoicing.

Sukkot has historical and agricultural significance. Historically,

Sukkot commemorates the forty-year period during which the Jews were

wandering in the desert, living in temporary shelters. But it is also a

harvest festival, a celebration of nature’s bounty.

A Sukkah means literally a booth and it refers to the make-shift

dwelling Jews are commanded to live in during this holiday in memory

of the period of wandering. The Hebrew pronouciation of Sukkot is "Sue

COAT." But the pronuciation I grew up with is the Yiddish one which

rhymes with "BOOK us."

Sukkot lasts for seven days. I didn’t know this, but no work is

permitted on the first and second day of the holiday. That explains why

I saw many orthodox Jews walking in Prospect Park yesteraday. Work is

allowed on the other days of the holiday.

The key to Sukkah construction is that it must be hastily assembled

like those temporary structrures the wandering Jews created in the

desert. It must have at least two and

half walls covered with a material that will not be blown by the wind.

The roof must be covered with tree branches, or other natural

materials. These materials must be left loose, not tied together

or tied down.

Stars should be visible through the roof.

Even as I admire this beautiful ritual, I feel no real connection

with it. It wasn’t part of my family tradition nor does it answer any

kind of spiritual longing on my part. But as a symbol of the Jew’s

plight of marginality (what Hannah Arendt would call "the Jew as

pariah") throughout history: the wandering Jew, the Other, it resonates

with me.

While learning about Sukkot is enormously interesting, I am very

uncomfortable with the evangelical aspect of Lubavitch Hasidism. Having

very strong beliefs is one thing but why must they insist on trying to

persuade others to have the same beliefs? It all seems somewhat

unJewish to me. What I like most about Judaism is the many ways there

are to be Jew: secular, athiest, intellectual, cultural, political,

reform, conservative, orthodox and hasidic, kabbalistic: there are

many ways to express one’s Judaism. Why is it necessary for

ultra-religious Jews to try to make other kinds of Jews more religious.

Why can’t they just let us be.