Sarah Deming met vocalist, composer, and multi-instrumentalist Jen Shyu at the Tea Lounge to discuss her composition “Red Sands, Raging Waters,” which she will perform at McCarren Hall in Williamsburg on Friday, March 26.

Sarah Deming met vocalist, composer, and multi-instrumentalist Jen Shyu at the Tea Lounge to discuss her composition “Red Sands, Raging Waters,” which she will perform at McCarren Hall in Williamsburg on Friday, March 26.

Based on an ancient Chinese narrative form called Shuo-chang (literally, “talk-sing”) and Brazilian poetry, “Red Sands, Raging Waters” features Portuguese, Mandarin, Tetum, and Taiwanese vocals (Shyu), dance (Satoshi Haga), clarinet (Ivan Barenbaum), cello (Daniel Levin), vibraphone (Chris Dingman), and percussion (Satoshi Takeshi). For more information, go here.

Sarah: Tell me about the genesis of this piece.

Jen: I got a commission to compose a new vocal work for the Jazz Gallery. At the time, I was traveling through China and Taiwan studying Shuo-chang and other traditional music, and the motif of flooding seemed to show up everywhere. After I gave a concert one night, we had to drive home through knee-deep rainwater. A month later, the day after I left China for Taiwan, someone read my Mayan horoscope and told me my sign was “Red Moon,” whose power is “Universal Water” and whose essence is to purify. The next day, I read an email from my host in China, saying that the day after I’d left, the pipes had burst in her apartment where I stayed! I thought of this story of a girl who caused flooding wherever she went. Then I learned this Chinese legend about a flood hero named Da Yu or “Yu the Great,” because my friend in Beijing was named after him. I collaborated with a poet named Patricia Magalhaes, who wrote Portuguese lyrics based on the Da Yu myth.

Sarah: What’s the myth about?

Jen: Yu’s father had unsuccessfully tried to save China from flooding by building dams. Yu succeeded by digging canals instead. Taoists love this story because it demonstrates the superiority of working with nature’s flow, rather than trying to subdue it. It’s also about the conflict between love and duty. Yu married his wife but he only spent five days with her before he had to leave. He told her to name their son Qi (啟) which means “Five Days” after the number of days they shared. They say Yu passed his own door three times while busy fighting the floods. The first time, his wife was giving birth. The second time, his son was taking his first steps. The third time, his son was waving at him and begging him to come home. But Yu never went inside. The same night I learned about Da Yu, a woman served me tea named after him, and she said, “He didn’t love his wife.” This was different than all historical accounts about him, which praised his abandoning his family in order to fight the flood waters. I wanted to give the wife and her suffering a voice in the piece, too.

Sarah: Is it important for the audience to understand all the words you are singing?

Jen: Well, I had a program with translations for the premiere of the piece. I’ve tried singing parts of it in English, but I felt it ruined the mystery. I like giving people a reason to absorb other cues, to look deeper. If they don’t understand the story, they can make up their own. When you go to a ritual, you don’t try to understand it – you just experience it. Maybe one day I’ll write some simple love songs, I don’t know! But I fear cliché. Even if the source material is transparent, like a folksong text, I want the music to retain some mystery. Just like people have mystery. At least, the people worth knowing.

Sarah: What kind of music did you grow up listening to?

Jen: Mostly classical. I played piano and violin, and my brother played piano and clarinet, so there was always a lot of practicing, and we entered competitions. My dad would make us these great cassette tapes with all the movements and names of classical pieces written out in his beautiful handwriting.

Sarah: When did you decide to use your own ancestry as an inspiration for your music?

Jen: My degree at Stanford was in classical singing, but I had started singing with some jazz ensembles, and I was reconsidering my path. I met this activist/saxophonist Francis Wong, who said to me, “Why don’t you check out your roots for inspiration?” Nobody had ever said this to me before. I dug out these Taiwanese folksongs my father had given me, and I started to learn and arrange them. Then I gave a demo to Steve Coleman in New York, and he told me, “You have a nice voice, but what do you want to do with it?” I told him I was thinking of going to Taiwan to study indigenous music, and he said, “What are you waiting for? You could die tomorrow.” He was right. We build up walls of excuses. I quit my teaching gig and broke the lease on my apartment. My parents were willing to help me pay for the trip, and I realized I couldn’t let pride stand in my way.

Sarah: I love the strength of your voice.

Jen: When I started singing as a kid it was in musical theatre, so I’ve always loved the strong voice. I find myself channeling Cassandra Wilson sometimes. I love the incredible depth and richness she has. You hear the air behind it. And even though what she does is difficult, she makes it sound easy, like water falling down. I’m over my “pretty singing” phase, and now I am interested in more primal emotion. Like these villagers I would listen to in Taiwan. They would be doing their work, chewing betelnut – none of this protective singer crap – and then they would open their mouths and the most beautiful sound would come out. It had nothing to do with technique. Knowledge comes in many different forms.

IN PRAISE OF YERBA MATE

IN PRAISE OF YERBA MATE

Like great music, yerba mate is meant to be shared. The Tea Lounge serves mate the way it’s served in South America: in a gourd with a metal straw called a bombilla. The gourd can be refilled many times, the mate becoming sweeter and milder with each re-steeping. Mate is high in Magnesium, slightly bitter, and strangely addictive. As the adorable barista Matthew remarked, “It’s caffeinated, but in a different way than coffee. It gives you a mellow feeling. The more you drink it, the more you want to drink.”

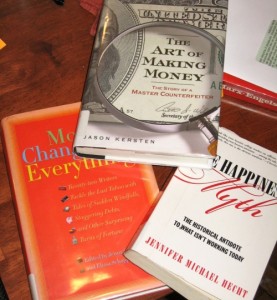

On April 15, 2010, Brooklyn Reading Works presents its monthly writers’ program on “tax day.” This happy accident, observed last summer in a casual conversation with John Guidry of Truth and Rocket Science over coffee, resulted in the idea for a panel called “The Truth and Money,” a reading and Q & A with three authors whose work has taken on money in some significant way.

On April 15, 2010, Brooklyn Reading Works presents its monthly writers’ program on “tax day.” This happy accident, observed last summer in a casual conversation with John Guidry of Truth and Rocket Science over coffee, resulted in the idea for a panel called “The Truth and Money,” a reading and Q & A with three authors whose work has taken on money in some significant way.