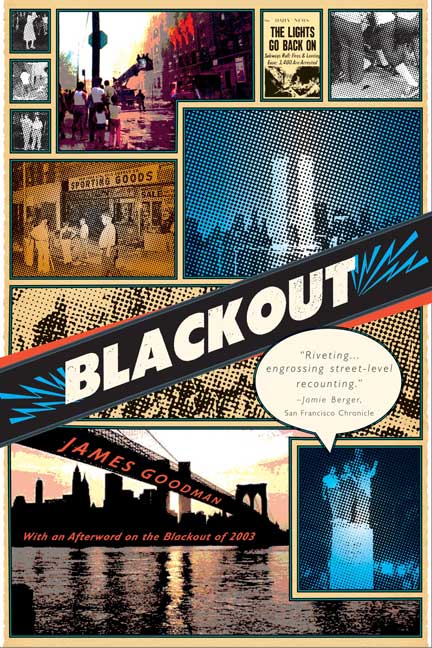

Today is the tenth anniversary of the 2003 Northeast Blackout. Pulitzer Prize finalist James Goodman, author of Blackout, wrote the following for the afterword of the paperback edition of his book.

Today is the tenth anniversary of the 2003 Northeast Blackout. Pulitzer Prize finalist James Goodman, author of Blackout, wrote the following for the afterword of the paperback edition of his book.

That July, they thought they knew why. And when the power failed twenty-six years later, in August 2003, they thought they knew again.

Not why the power failed.

No one knew that, and once people were assured that the blackout was just a blackout–not sabotage or a bomb–few peopler eally cared. Initial reports thatlightning had caused it (“just like 1977,” news-people said) werequickly discredited. The politicians who scrambled to the nearest microphone to blame regulation or deregulation,oil-men or tree-huggers, Democrats or Republicans, were by and largeignored. Instant analysis gave way toinvestigative reporting, and for weeks each day’s papers carried the latesttheory: overgrown trees; equipment failure; human errror; commuciationsmishmash; computer crashes; clueless system operators; the absence of uniformoperating standards and procedures; balkanized oversight; unenforcedregulations; federal rules violations; utility mismanagement; the structure ofthe industry; the politics of energy policy; or all of the above: thesuperpower’s third-world power grid.

Officials in Washington, Ottawa, and eight state capitals ordered investigations. Utilities pointed fingers at one another. Experts argued. But the people who knew themost said the least, realizing that it would be months before investigatorscould collect, organize, and interpret the data–tens of thousands of bits andpieces of information–that might allow them to trace, millisecond by millisecond, the cascade of events that transformed the routine failure of afew power lines into a history-making electrical disaster.

New Yorkers didn’t know why the power failed.

What they knew was why, when it did, no one had looted.

They were sure they knew, and it felt really good to say.

The city had changed.

Back in the 1970s, New York had been in desperate straits, wracked by stagflation, strikes, arson, drugs, graffiti,cynicism, a serial killer, stinking subways, white flight, gas lines, high crime, fiscal crisis, and racial strife.Now it was a different place.

Despite the recession and the fallout from the attack on the World Trade Center, the economy was fundamentally sound. The population had topped eight million in 2000, and it continued to grow. New immigrants had revitalized several struggling neighborhoods; artists had revitalized others. A record number ofconstruction workers had built a record numbers of new homes, and with aid from the city, they had built some of those homes for first-time homeowners in theSouth Bronx, Harlem, even Bushwick.

It was a new city, pundits said, a city remade. Families were more stable. Streets were cleaner. In the parks, flowers bloomed. The police were tougher. Drug use was on the wane. New Yorkers cared for one another and for New York. Respect for the law had grown. Violent crime was at all-timelows. Selfishness and detachment wereout; cooperation, responsibility, and compassion were in vogue. The subways were safe, and often on time. And thanksto Osama Bin Laden and Saddam Hussein, black and white New Yorkers were finallyon the same side of the color line.

Some stressed the new civility.

Some stressed the half-life of a long economic boom.

Some stressed the years of tough policing, and their dark side, fear.

Everyone mentioned the difference that the time of day might have made: The power failed at 4:30 in the afternoon, giving the police three and a half hours to mobilize before sunset and another half hourbefore dark.

The list of reasons was long,but next to no one argued about which reason was right. People don’t get as worked up when bad things don’t happen as when they do. In 1977, people had refused to acknowledge that there might be more than one reason why people looted. In 2003, people readily acknowledged that there might be more than one reason why they did not. But, in a way, they were not acknowledging much: almost all the small reasons added up to one big reason, the reason that felt so good to say:

New York, and New Yorkers, had changed.

What a difference a day had made.

On August 13, and for months before that, most of the talk and writing about the city had been grim: the billion-dollar budget deficit; the fitful recovery from recession; the corporate relocations; thedecline in tourism; the narrowly averted transit strike; the layoffs of thousands of city workers; the hike in taxes, transit fares, and fees; theclosing of firehouses, subway token booths, branch libraries, and outer-borough zoos. Violent crime remained low, but two years after September 11, most New Yorkers expected another terrorist attack, and many said they had simply learned to live with anxiety andfear.

In fact, until the afternoon of August 14, hardly a day had passed without a commentator asking, ”Are we living through the 1970s all over again?”

Then the power failed.

There was some panic, and some price-gouging. After the sun went down,there were scattered incidents of looting. But the vast majority of people rose to the occasion. Even Con Edison came through. The utility had done “as good a job ascould be hoped for,” the mayor said.

Things were not so bad after all. Certainly nothing like the 1970s. On the contrary, things were good. And New Yorkers were good too.

That was a comforting comparison, and it lay atthe heart of a comforting explanation. But it ignored at least one inconvenient fact: When the power failed in July 1977, most people did pretty much the same thing they had done when the powerfailed in November 1965, and would do again when the power failed in August 2003. Some of them did the exact samethings: They evacuated subway trains; hung out on stoops; directed traffic; hosted blackout parties; bagged patients on respirators; walked for miles andmiles; carried water to the elderly and infirm; cooked and ate food they feared would spoil.

In 1977, unlike 1965 and 2003, many people looted, and afterward people agued about why. But the vast majority of people—most everyone–in every neighborhood inthe city rose to the occasion, deporting themselves admirably, making theirmayor proud.

It was no easier to know for sure why people did not loot in 2003 than it was toknow why they did in 1977.

It was even harder to explain the reasons with confidence on the news the very evening of the blackout or in the newspapers the next day. Everyone who has ever been asked to analyze an event while it was still happening, or to explain the historical significance of the day’s top story,will sympathize with and give credit to all those who tried. The mayor was one who tried: “New Yorkers” he said, “showed that the city that burned in the 70s . . .is now a very different place.”

And the mayor was right. The differences are real. The looting was horrible. The city was burning. There is no denying that things have changed. But we should be wary of thepundits’ tale of two cities—the sick city and the healthy city; the lean years and the fat years; the bad New Yorkers and the good. Or any other story that suggests thateverything or everyone is either one thing or another, that everything or everyone has changed, or remained the same.

New York was a cold place in July 1977, and a caring place. Among those who cared were the people whoargued about the looting. Sure, somewhere opportunists and ideologues seeking to score political points. But many others, on both sides of the argument, cared deeply about the welfare of the city. Many also cared deeply about the welfare ofthe looters.

New York was a dangerous place in 1977, and it was a safe place. It was a kind place and a cruel place. It was athrilling place and a frightening place. It could be dark in broad daylight,and bright in the dark. Many people were miserable, and many people were having the time of their lives.

It is all that now. And perhaps what is most thrilling and most frightening is how in a fraction of a second, for particular people in particular places at particular points in time, it can change from one to the other.

Just ask the people who, on the afternoon of August 14, 2003, were stuck, without a clue, in an elevator in the EmpireState Building. One of them was rescued by a detective who rappelled down the shaft, put a harness around him, andhauled him up five floors to safety. Ask the people whose blackout celebrations were spoiled by their careless use ofcandles. In Greenpoint, two of them werepulled out of the flames by firemen moments before they would have died. Ask all the people who, in that first uncertain hour after the power failed, were suddenly separated from a parent,spouse, or child in the impatient mass of people converging on the 38th Street ferry terminal or crossing an East River bridge.

Or ask anyone who has simply been smiled upon by a stranger on a city sidewalk when a smile was the only thing in the city that would do.

Or anyone who saw or heard those highjacked planes in their final seconds off light and remembers—everyone remembers–the brilliance of the sky over thecity that morning: a blinding blue.

Contradictions. Absolutely. A city is large, and it contains multitudes. When we think about it, when we talk about it, when we write about it, when we argue about it–when we try to figure ou twhy our friends and neighbors, let alone total strangers, do the things that they do–we owe it to the city, and to ourselves, to be true to those contradictions. They are our contradictions too.