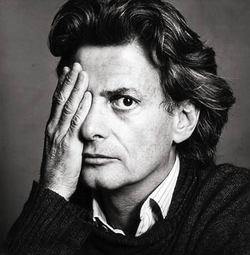

Richard Avedon, the photography legend, died a year ago on October 1, 2004, of cerebral

Richard Avedon, the photography legend, died a year ago on October 1, 2004, of cerebral

hemmorage while shooting pictures for The New Yorker Magazine in Texas

(further proof that the lone star state is a place to avoid). He was a

very energetic 81 years old.

Avedon was one of my heroes, and many of his photographs rank among my favorites.

Especially the close-up of Marian Anderson’s face, eyes shut tight, her

singing mouth a tall-oval. Or the double portrait of Phillip Glass and

Chuck Close sitting crossed legged in chairs. Who can forget the the

panoramic view of the Chicago Seven or the gigantic print of June Leaf,

looking so earthy, so sexy, and real, that it took my breath

away when I saw it at Avedon’s exhibition at the Metropolitan all

those years ago.

I never heard Avedon speak, and knows

little about his biography. I do, however, remember that he, like

Diane Arbus, was the child of a clothing store owner. He was a born and

bred New Yorker, who gracefully straddled the "high/low" worlds of

advertising, magazines and fine art. He gave money to civil rights and

other good causes, and was the inspiration for the debonair

photographer played by Fred Astaire in "Funny Face," which I viewed recently. Avedon had a

difficult relationship with his father, a Russian Jew, and took raw,

loving pictures of him as he lay dying.

Avedon was also a big

influence on my husband. The influence is most evident in the huge black

and white portraits of friends, street people, and teen mothers that he was printing in his Ludlow Street darkroom back when I met him in 1986. It is the directness and honesty of Avedon’s work

that my husband admired: "His pictures really let the subjects speak for

themselves," he says. "The consistency of the work and the sameness

from picture to picture really help differentiate the subjects from one

another."

Like much portraiture, Avedon’s pictures are also

very much about the artist himself. They reveal a great deal about his

process and his interests: "Sometimes I think all my pictures are just

pictures of me," Avedon told an interviewer. "My concern is the human

predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may simply be

my own."

It’s so strange when a celebrity hero dies. You don’t

really know what to do with the grief. The world seems a little

emptier, a little sad. But there’s no shivah to sit, no funeral to

attend. It’s like when Marlon Brando died — it was the week after

Reagan’s funeral and all the flags were flying at half-mast. I kept pretending that the flags were flying for Marlon and his immortal

gang of characters that will live forever: Stanley Kowolski, Vito

Corleone, the biker in "The Wild One, and last but not least, Terry

Mallone in "On the Waterfront."

Likewise, Avedon leaves behind

indelible images that we, and those yet to be born, have to keep.

Forever. They distill a kind of inner truth about the artists,

performers, cowboys, politicians, activists, fashion models and writers

who were his subjects. And yet, as Avedon himself said, "All

photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth."

Goodbye Avedon. Thank you for showing us how to see.

You managed to make me laugh during a nice tribute – the Texas comment. Interesting thoughts – I haven’t had a celebrity hero die and I haven’t really thought about it until now.